Designing an MMO - Server Architecture

Let’s talk about server architecture.

Requirements are going to be different for any given type of game. Single-player games might not need any kind of server architecture, or might just report back to a leaderboard service. A multiplayer-lobby game might host instances for each lobby - in a shooter, for example, you could have a single instance handling a match with eight players. A game server might run multiple instances, and you can easily spin up new game servers if you need more instances than the server can handle.

Besides computing resources, though, an MMO has to juggle an additional resource: connections. Each client connection consumes a certain amount of server resources. But if a server can handle only 500 connections, what happens when a thousand players try to connect to the same instance?

Instances

Let’s take a step back and talk about instances. An “instance” is a way of breaking up the entire game world, so we can run a piece of the world at a time. Each match in a multiplayer-lobby game would be its own instance; in larger MMOs, you might have a geographical area associated with an instance. When you walk into a city, there’s a loading screen, and you connect to the city’s instance.

An instance might run on its own physical server, or a physical server might run multiple instances, depending on the load.

But that makes it difficult to scale. What happens when there’s a big event in one particular instance, causing hundreds or thousands of players to swarm in? You could increase the server’s resources, but that’s expensive and not easy to do quickly.

Instead, we want to break things up and distribute them around, so that a single instance’s load can be spread across multiple servers. If we need to support more players, we can use a load balancer to add more servers to the instance.

There’s another important question of maintaining the user’s connection as they jump between instances: are they forced to disconnect and reconnect to the game server that’s hosting the new instance?

Our architecture will address those concerns.

Connection Servers

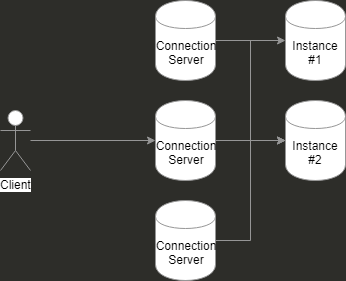

What happens when we separate out the connection servers?

For one thing, we take some of the load off the game servers, since they don’t also have to manage the connections. I’m not certain off the top of my head if that has a practical effect in terms of scaling the connection servers separately from the game servers, but it does achieve one thing: Clients can remain connected while they seamlessly transition from one game server to another.

The connection servers will handle authentication and reconnection, if the client gets disconnected. They’ll also keep track of which instance the client is connected to. When the client sends an action, the connection server will tag it with the appropriate instance and drop it in a queue.

Game Servers

Instead of running multiple instances per game server, or even one instance per server, we’re going to allow a server to handle actions for one or more instances.

The game servers will listen to the queue where the connection servers are sending actions. When they see one for an instance they are managing, they’ll pick it up.

This allows us to easily spin up a new game server for an instance under load by just adding it to the queue. Whichever server is ready will pick up the pending action, distributing the work across the cluster.

Similarly, when an action has been resolved and written to the global state, the finalized action will be dropped in another queue to send back to the connection servers. Any connection servers with a client in that instance will pick up the message and forward it along.

Whoa, Hold Up

This architecture makes sense at scale. But we’re only going to have a handful of clients during development, and maybe a few dozen during early testing. Building out this much functionality would be way overboard for where we are in the project.

For right now, we’ll build this to run as a single server, but we’ll split things up logically to make it easier on ourselves when it comes time to break this up to run as multiple services.

We’ll create a Connection Server that will host the websocket. This server will import a Game Server Wrapper, to which it will send and receive actions. The Connection Server doesn’t care if the Wrapper is actually using queues (it isn’t) or really just importing the Game Server module and calling it directly. But when it comes time to break the two apart, all we have to do is replace the Wrapper with one that uses queues.

Conclusions

We aren’t spending too much time on these details right now, as this will mostly be relevant when the game is released and needs to be scaled. But it’s helpful to plan ahead a little bit so we’re prepared when that time comes!

Let me know what you think of this article on twitter @jonwinsley or leave a comment below!